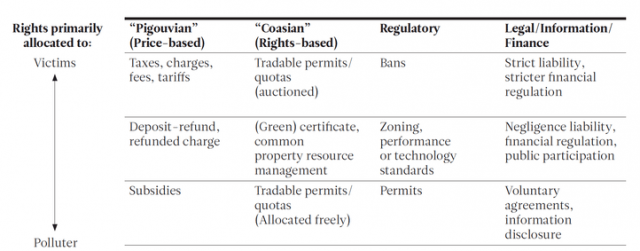

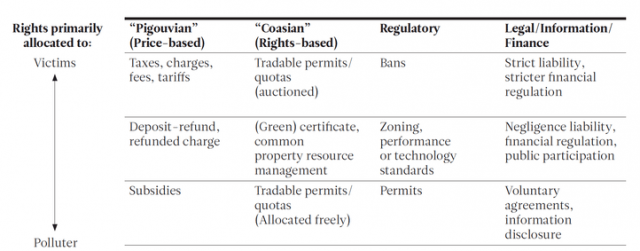

Classifying policies by type and by rights assigned to polluters or victims.

By Thomas Sterner and Gernot Wagner

The Earth has its limits. With growing population and wealth but finite natural resources, we must consider how to sustain humanity without causing abrupt—potentially disastrous—environmental change. In 2009, a group of Earth system and environmental scientists developed a framework with which to think about global sustainability. They concluded that Earth has nine systems, dubbed “planetary boundaries,” that are essential for environmental stability. According to them, “transgressing one or more planetary boundaries may be deleterious or even catastrophic.” Humankind, they conclude, already has overstepped three categories: climate change, rate of biodiversity loss, and changes to the global nitrogen cycle.

That’s where smart policy design can help. But in the “Anthropocene”—an era dominated by human activity—designing effective policies for global sustainability is daunting. This is because the threats are “global, long-run, uncertain, and potentially irreversible.”

How, then, do we think about practical policy design? And what can we say that might help policymakers guide humanity’s fate on Earth?

These were the questions we, along with more than two dozen coauthors, sought to answer at a workshop convened at the University of Gothenburg in December 2016.

The mission was to bring together an eclectic mix of policy-focused academics from a range of different disciplines to tease out areas of agreement and to identify a roadmap for how to tackle policy design in the Anthropocene. Those in the room included senior academics from the sciences—biology, ecology, climate science, and earth’s systems modeling—and the social sciences, like anthropology, sociology, and economics.

The result was a sweeping perspective published earlier this year in Nature Sustainability.

Policymakers in many countries are daunted by the challenge of creating effective solutions, besieged by lobbyists and special interests. They often feel they don’t know what policy instruments they have at their disposal, nor do they know which ones really work. In fact, the menu of possible policy instruments is large, perhaps overwhelmingly so. To guide policymakers and make sense of it all, we look at two dimensions: how the instruments are structured and who pays.

Every conceivable environmental policy solution can be placed somewhere on the table.

There are vast differences across these policy instruments. “Information disclosures” are a far cry from outright bans. The former assigns the right to pollute squarely to polluters, merely asking them to disclose certain information. Bans, meanwhile, are akin to pricing pollution at an infinite cost, assigning rights squarely to the victims.

There are also important commonalities. Taxes and subsidies are two sides of the same coin. Both are price-based instruments. The difference? Taxes make polluters pay. Subsidies, while capable of achieving the same overall environmental objective in principle, instead compensate the polluter for moving to less polluting, cleaner activities. The difference is largely one of political economy and, ultimately, politics.

Something similar goes for rights-based interventions. The important fact there is that one policy instrument—tradable permits—can span the entire spectrum, from allocating rights solely to polluters on the one hand to allocating them to victims on the other.

When it comes to dealing with multiple planetary boundaries, we face the additional challenge of understanding how ecology and politics create links between different areas, and we must realize that some policies may be designed to deal with several planetary boundaries at once. However, we also must be wary of policies that may help deal with one problem but risk aggravating others.

How, then, to choose among these instruments? That is where academics typically leave the room and politicians enter. Policy-focused academics, of course, would do no such thing. The table might provide an important, intellectual foundation. The most important work, however, is all about choosing and designing the appropriate instrument, in the right context. For example, discussing emissions trading in theory is one thing. Doing so in practice is quite another. The devil—and much of the most important work—is, as so often, in the details. To help, we identified seven guiding principles:

- Inherent complexities necessitate interdisciplinary collaboration in the design of appropriate policies and governance systems.

- To identify the appropriate strength and type of policy, it is important to ascertain how serious the environmental problems are. If possible to measure, this could be given by the distance to the various boundaries.

- Links across planetary boundaries often necessitate considering two or more of them together—both because policy approaches tackling one boundary may lead to “ancillary” benefits elsewhere, and because of potential conflicts, where a policy that mitigates human impacts on one dimension exacerbates threats to another.

- Despite the novelty and complexity of the task, several well-known policy instruments exist. The challenge thus is not to invent entirely new approaches, but to select and design appropriate policies given specific scientific, societal, and political contexts.

- Instrument selection depends on a proper diagnosis of the socioeconomic cause(s) underlying the problem, focused on the most important points of leverage.

- Effective policy choice and design need to be based on efficiency, achieving desired outcome at lowest costs, but must also consider “political” criteria such as the distribution of costs and resistance by powerful vested interests.

- Finally, global problems need policy instruments and agreements that are operational at both international and local levels, to ensure not only efficient outcomes but also effective jurisdiction and governance.

These principles are surely not the final word. However, we believe they are a good way to conceptualize the problem and think about possible solutions.

This article was first published in the 60th anniversary edition of RFF’s Resources Magazine.

Tagged: Anthropocene, featured, Media, Perspective